- Home

- Michael Traikos

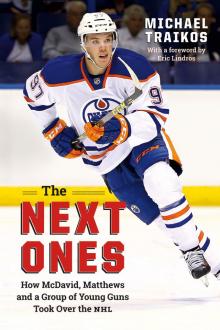

The Next Ones

The Next Ones Read online

The Next Ones

The

Next

Ones

How McDavid, Matthews and a Group of Young Guns Took Over the NHL

Michael Traikos

Copyright © 2018 Michael Traikos

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, www.accesscopyright.ca, 1-800-893-5777, [email protected].

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC, V0N 2H0

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Edited by Silas White

Indexed by Allie Turner

Text design by Shed Simas / Onça Design

Cover design by Setareh Ashrafologhalai

Printed and bound in Canada

Douglas and McIntyre (2013) Ltd. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Traikos, Michael, author

The next ones : how McDavid, Matthews and a group of young guns

took over the NHL / Michael Traikos.

Includes index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77162-198-4 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77162-199-1 (HTML)

1. Hockey players--Biography. 2. National Hockey League. I. Title.

GV848.5.A1T73 2018796.962092’2C2018-903087-9

C2018-903088-7

Contents

ix Foreword

1 Introduction

4 Mark Scheifele

24 Johnny Gaudreau

46 Matt Murray

68 Aaron Ekblad

90 William Nylander

108 Jack Eichel

128 Connor McDavid

150 Mitch Marner

172 Auston Matthews

196 Patrik Laine

215 Conclusion

217 Acknowledgements

218 Credits

219 Index

227 About the Author

For Danielle, my density—I mean, destiny

In memory of Fanny (Baba) Misketis, who passed away while this book was being written and who was so heavily involved in my own origin story.

Foreword

The first time I saw Connor McDavid play live was in the 2015 World Junior Championships in Toronto, where Canada won gold.

I’ll never forget it.

It was the championship final and Canada was leading 2–1 against Russia in the second period when McDavid scored a goal that caused my jaw to drop. Taking a pass in the middle of the ice, he rocketed past two defenders for a breakaway and then snuck a shot through the Russian goalie’s five-hole.

Everything about the goal was amazing.

Some players have two or three gears. McDavid seemed to have five or six with a nitro boost to spare. It was spectacular. I had seen his highlights on TV and YouTube. But watching him live was completely different. You got a real sense of his speed and skill and everything else that makes him so special.

All the players in this book share that same ability.

This is an amazing time for hockey. I don’t think the game has ever been this good. The skill on display is really something else. The players are not only faster and stronger, but they’re doing things that I didn’t think were possible when I was playing.

You see smaller players like Mitch Marner or Johnny Gaudreau deke circles around defencemen and you can’t help but marvel at what they are able to accomplish at their size. Back in the day, those guys simply weren’t getting opportunities. Now, they’re some of the NHL’s brightest stars—and rightfully so.

What’s really stood out from watching these players emerge—and reading about their origin stories—is how different each of them is. They play the game differently. And they’ve all followed a different path. In Auston Matthews’s case, he had to carve out a path on his own. And that’s what makes this next generation of next ones so impressive.

Like Mario Lemieux and Gordie Howe before me, I may have had an impact on the next generation of superstars through my on- and off-ice actions. But this isn’t a cookie-cutter league. What works for one player doesn’t always work for another.

Sure, it takes talent and a ton of hard work to even get to the NHL. But to become a star takes something else. Each of these players is so special, not just in his ability but in his drive. Whether it’s McDavid taking hundreds of shots every day or Jack Eichel failing and then persevering against much older competition, nothing came easy to any of these players.

No one was an overnight success. No one got handed anything without putting in a ton of effort.

For most of them, they’ve always been in the spotlight. They’ve always had a target on their backs. But each one of them persevered to become one of the best in his generation. And they did it their own way. That’s what’s so interesting about this book.

Both McDavid and Aaron Ekblad entered the Ontario Hockey League (OHL) a year earlier than normal. I went in at age sixteen. Matthews grew up in Arizona and decided to play in Switzerland rather than in college. Matthews is a strong kid. He knew he could handle himself against men. You look at his neck and he’s just going to get bigger and stronger.

That isn’t the case with Marner and Gaudreau. You look at them and you wonder, how is it that they got here? And when you find out, you appreciate their journey even more.

All my life, everyone has given me the benefit of the doubt because of my physical appearance. I was always one of the biggest. With Marner and Gaudreau, it’s the opposite. They’ve been doubted and disregarded almost every step of the way. In some ways, it’s probably helped them get this far.

Even William Nylander had it hard. Don’t think he was drafted just because his dad played in the NHL. In some ways, it was probably more difficult playing in his father’s shadow. I can tell you this much: as good as Michael Nylander was, his son might be even more talented. And that’s saying something.

And then there’s Mark Scheifele. You look at him today and he’s such a dominating centre. You figure he’s always been this way. But then you realize it took him a long time to even get to the NHL. To me, that’s even more impressive. He’s like John LeClair. He was one of the best wingers I ever played with, but it took him a while to figure out just how good he was. When he eventually did, he and Mikael Renberg and I did great things together.

It’s another way of saying that not every player’s journey is a straight line. There are bumps and detours along the way. That goes for first-line stars as much as it does for the fourth-line grinders.

From McDavid to Matthews, I think it’s great for hockey that there are so many young players already taking over the league. I wish them all the best. I really do.

And I can’t wait to see the next generation of next ones who will follow in their path.

— Eric Lindros

Eric Lindros, who was a No. 1 overall pick in the 1991 draft, scored 372 goals and 865 points in 760 games over a Hall of Fame career that spanned thirteen years. A former Philadelphia Flyers captain, he won the Hart Memorial Trophy in 1994–95 and had his famed No. 88 jersey retired by the franchise in 2017.

Introduction

It was supposed to be a gimmick. It ended up becoming a game-changer.

When the NHL and the NHL Players’ Association decided to sta

ge another World Cup of Hockey in the fall of 2016, the usual six powerhouses (Canada, the United States, Russia, Sweden, Finland and the Czech Republic) participated. But in the name of inclusion, the leftover European nations were lumped together on Team Euro, while Team North America collected the best Canadian- and American-born players who were age twenty-three or younger.

Whereas Team Euro surprised everyone and made the final against Canada, the young Team North America stars didn’t even advance past the round robin. But with its black-and-bright-orange colour scheme and live-fast-die-young playing style, Team North America was the highlight of the tournament.

The kids were lightning quick, supremely skilled and full of spunk. They were also very, very fun. When the 5-foot-9, 157-pound Johnny Gaudreau was asked if he was worried about other teams trying to intimidate the younger players with bodychecks and physical play, he replied, “It’s tough to hit someone you can’t catch.”

The idea for this book came from covering Team North America from the start of training camp to their final thrilling game of that two-week tournament. But really, the World Cup of Hockey was just the beginning.

A few weeks after Connor McDavid and Auston Matthews were teammates for the first—and last—time at an international event, the one hundredth year of the NHL began. It truly was a year for the ages. In celebrating the past, the league also looked forward to the future in a season where the kids took over.

McDavid, who was twenty years old and playing in his first full season, led all scorers with 100 points and won both the Hart Memorial Trophy and the Ted Lindsay Award as MVP. A teenaged Matthews won the Calder Trophy as the league’s top rookie, while also tying for second among all players with 40 goals. Matt Murray, who was twenty-two when he won a Stanley Cup the previous spring, backstopped the Pittsburgh Penguins to a second consecutive championship while still technically a rookie. By the end of the season, seven of the top thirty scorers—including four of the top ten—were twenty-three years old or younger.

This isn’t a top-ten list of the NHL’s young players. There are names here that you will agree with and some that you will question. You might, for instance, be wondering why Vancouver’s Brock Boeser or Edmonton’s Leon Draisaitl were not included, or why so-and-so is here and Boston’s David Pastrnak or Colorado’s Nathan MacKinnon are not. I could go on and on.

From Florida’s Aleksander Barkov and Columbus’s Zach Werenski to Arizona’s Clayton Keller and the Islanders’ Michael Barzal, there are more than enough supremely talented young players to warrant another ten chapters. That’s how stacked the league is with young talent.

All I’ll say is that the names I chose made sense to me when the book was conceived and I think they still make sense now. At the same time, this isn’t a book about what the players have done in the NHL. This is what they did to get there. Consider this book an origin story, where instead of Peter Parker getting bitten by a radioactive spider, it’s how Matthews was bitten by the hockey bug while growing up in Scottsdale, Arizona.

Each story is different. Whereas Aaron Ekblad was always the biggest and strongest kid even while playing two years above his age group, a late bloomer like Mark Scheifele was continuously knocked around as he fought through obstacle after obstacle on his longer and more arduous path to the NHL.

You’ll notice the narratives are far different than if this book had been written ten or twenty years ago. This generation isn’t like the generation before it. The players didn’t necessarily grow up skating on frozen ponds like Bobby Orr did. McDavid learned how to become the fastest and most agile hockey player in the world by strapping on rollerblades and deking around paint cans in his parents’ two-car garage. Patrik Laine shot pucks at pop cans, William Nylander shot pucks at his dad’s NHL buddies and Johnny Gaudreau chased Skittles around the ice.

Obvious thanks go to the players, their families and friends, and former coaches and teammates for helping reveal the secrets behind what has made each person so special. This book could not have been written without their co-operation, something I valued whether I was travelling to Thunder Bay to spend a low-key day with the Stanley Cup and Murray, or watching old YouTube clips of a pint-sized Mitch Marner with his parents.

Last but not least, thank you to whoever has purchased and decided to read my first book. I hope you enjoy these stories as much as I enjoy telling them.

— Michael Traikos, January 2018

Mark Scheifele

Mark Scheifele and St. Louis Blues’ Patrik Berglund prepare for a faceoff in 2018. AP Photo/Billy Hurst

Winnipeg Jets

» № 55 «

Position

Centre

Shoots

Right

Height

6′3″

Weight

207 lb

Born

March 15, 1993

Birthplace

Kitchener, ON, CAN

Draft

2011 WPG, 1st rd, 7th pk (7th overall)

Mark Scheifele

Oftentimes in hockey, greatness is apparent the moment you see it. There’s an “It” factor, something you can’t always explain or fully understand, but that is undeniable to both the seasoned scout and casual fan watching for the first time. The scouts who first laid eyes on Crosby and McDavid and other phenoms knew they were seeing something special, even when the players were at their very youngest. These were hockey prodigies who were not only playing one or two years above their age level, but were dominating the competition. They made the game look easy.

When scouts first laid their eyes on Mark Scheifele, they didn’t see someone who made the sport look easy. If anything, he made it look hard. “A tall, lanky kid who falls over a lot and is weak” was the scouting report Scheifele heard over and over again when he was trying to get drafted into the Ontario Hockey League (OHL). “I heard he got hurt a lot,” said Barrie Colts general manager Jason Ford. “Someone said every game they went to he was lying on the ice.”

That’s not the image of Scheifele today. The late bloomer who was cut from his first junior training camp and sent back to the OHL twice is now “one of the best centres in the league,” according to Toronto Maple Leafs and Team Canada head coach Mike Babcock. How did Scheifele do it? How did a player go from potential bust to “one of the best centres in the league”? He did it by becoming, in his own words, “a hockey nerd.”

It is a weekday in May and Scheifele is sitting on the eleventh floor of an office in the cafeteria, a white long-sleeved shirt pulled tight over bulging arm and shoulder muscles. Hearing that Scheifele was once a player who was weak and easily pushed around is sort of like being told that Captain America was once too scrawny and too frail to enlist in World War II. The fictional Steve Rogers received injections of a super-serum to become Captain America, a near-perfect human with super strength, stamina and intelligence. Scheifele developed those same assets, but he got them the hard way.

“Just passion. I’m very, very, very competitive,” said Scheifele. “It’s pretty much that winning satisfies me. I don’t want to lose. So if I pick up a badminton racquet and play you, and you beat me, you’re not beating me again. So if you go and train for an hour that day, I’m training for seven hours so that next time I’m beating you.”

In a few days, he will represent Canada at the Ice Hockey World Championship in Cologne, Germany, and Paris, France. But on this day, the Winnipeg Jets centre is talking about trying to conquer the world on an individual level. Scheifele, who just turned twenty-four years old, says he wants to be better than Crosby, who just won his third Stanley Cup, and better than McDavid, who just won the Art Ross Trophy (he would win another in 2017–18) and is about to be named league MVP. Four other players finished ahead of Scheifele in the NHL scoring race in 2016–17. He wants to be better than them too.

It’s not just lip service. A day earlier, he was on the ice working with skills coach Adam Oates. That was after he spent the morning training with

high-performance coach and former NHLer Gary Roberts. When Scheifele’s not on the ice or in the gym, the self-professed “hockey nerd” is watching hockey highlights and picking apart subtleties of the game that might give him even the slightest advantage.

“I want to be the best,” said Scheifele. “I’m not satisfied with just being in the NHL. I wanted to be a second-line centre in Winnipeg, then a top-twenty scorer in the league, then the top ten, so obviously my goals are higher now. I want to win a scoring title, win a Stanley Cup, win an Art Ross, whatever it is. My goals keep readjusting themselves. But the end goal is to win a Stanley Cup and be MVP of the playoffs.”

Scheifele would fall short of that goal in 2018, when the Jets lost to the Vegas Golden Knights in the Western Conference final. But with 14 goals in 17 playoff games, his star continues to burn bright. It’s not surprising, considering that a year earlier he finished seventh in league scoring with 32 goals and 82 points in 79 games. And yet, it sort of is when you consider the long road he took to even getting to the NHL.

It’s a lesson to any kid who gets cut from a team or is told he is too weak, too slow, too average to be great. Scheifele heard it all and he turned it into motivation. He wasn’t the most naturally talented; he was the kid who everyone doubted had decided at an early age to be the most committed and hardest working. He was the rookie who took shots until his fingers bled from the blisters and who insisted on drinking root beer instead of alcohol at an initiation party. Today, it’s finally paying off. The late bloomer has blossomed.

“It’s a real learning curve. It doesn’t happen overnight. It takes time, right?” said Mark’s dad, Brad. “The sky’s the limit for every player, but it’s nice to see that his game is coming along. It’s been a beautiful ride for Mark. When you look at the players who were taken in his draft, Mark has pretty much been number one.”

The Next Ones

The Next Ones